By James King, Library Director at Salisbury School

James Mars didn’t complain of “many things,” but one thing troubled him his entire life: the lack of “opportunity to go to school as much as I should, for all the books I ever had in school were a spelling-book, a primer, a Testament, a reading-book called Third Part, and after that a Columbian Orator.” Mr. Mars would go on to write his own book and it seems a fitting tribute to this remarkable man for his story to now further the education of others.

When Salisbury School history teacher Rhonan Mokriski asked me to help with the Searching for Slavery course, I was thrilled to take part. As the school’s librarian, I had worked with the history department on multiple occasions and was excited about the prospect of a more extensive collaboration. Over the last year, my contribution to the class has been in three parts: finding, providing, and showcasing research resources and media creation applications; researching with students during class time; and contributing articles and comments to the class’s Microsoft Teams channel.

I began by building our collection of books on enslaved people in Connecticut and New England. Rhonan recommended many titles; some focused on the history of slavery in the region (e.g. African American Connecticut Explored; African American Heritage in the Upper Housatonic Valley; Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England), while others looked at the lives of the enslaved (e.g., A Free Woman on God’s Earth, The True Story of Elizabeth ‘Mumbet’ Freeman; A True Story of Freedom: Venture Smith’s Colonial Connecticut). These texts have been foundational to each group in the class, as they focus on topics such as Venture Smith, the Cesar Family, and Black soldiers in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars.

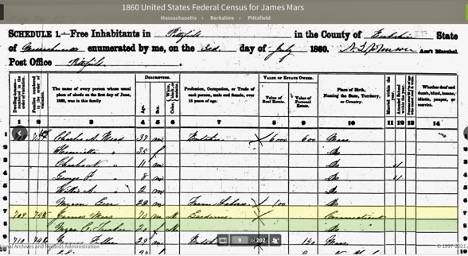

In terms of digital resources, Ancestry Classroom has been indispensable. Our Ancestry K12 Grant allows students access not only to Ancestry Classroom but also to Fold 3, a military records database, and to Newspapers.com. Students use these resources to uncover the lives of enslaved people and their families by reading “against the grain” of the official records that recorded their lives. By combing census, military, and other available records, students have been able to chart the family trees of members of the Mars and Cesar families.

Helping students navigate these resources has been one of the most rewarding parts of this class. Students typically sit in the back of the library, spread out in our stuffed chairs with laptops at the ready. Groups work on social media posts, create Wikipedia pages, contact politicians, meet with potential interviewees, and tackle other tasks within this multifaceted project. Most days I work with students focusing on family genealogies. I chat with them about their findings and then join the search to discover more about the lives of formerly enslaved people and their families. When things are clicking, genealogical research has the thrill of a treasure hunt.

On one occasion, a student and I used census records to chart James Mars’s movement around New England. Inconsistent transcriptions of his name hindered our initial search as we followed him over three decades of census records. We’ve found such errors to be common in the official governmental and military records of African Americans—a troubling reminder of their marginalization both in society and in the historical record. During another class session, a student and I cross-referenced Ancestry and Fold 3 to locate another Mars relative, Ganalvin Mars of the 29th Regiment of Connecticut Colored Infantry. As the service record shows, his name was sometimes written as Ganalvin, Gnalvin, or, as transcribed by Ancestry, Gralvin. The name appears to have been passed down as a family name, with Mabel Mars naming her son Genalvin more than seventy years later in 1918. Variations in the recording of African American names, compounded by the common difficulty of reading digitized handwritten documents, have been surmountable hurdles to uncovering the lives of these inspiring local individuals and families.

Along with helping students navigate electronic resources, I’ve also introduced them to technologies for creating and sharing their projects. Adobe Spark has provided a particularly helpful platform for students to share what they’ve learned. Hurst Thompson, for example, used Spark to great effect in his post on the life of Venture Smith. The application perfectly suited his need to communicate a story through both words and pictures. Spark is both visually engaging and easy to use. After a brief introduction to the platform, Hurst was off and running. Since Hurst’s first foray into Spark, I’ve had the opportunity to introduce the application to multiple classes, including another History class presenting on sometimes overlooked African American trailblazers in film, literature, music, and politics.

Lastly, I support the class’s Microsoft Teams channel. As an embedded librarian, I’m able to view student work, posts articles, and contribute to the rich dialogues in each class subgroup. The platform has been a particularly helpful means for sharing articles and digital artifacts from JSTOR and other databases and online resources. Whereas my past communications and resource suggestions would largely have been limited to the teacher, I now communicate directly with individual students and share articles with class groups. Over the last year, the platform has provided a simple and effective way to follow up on class discussions and add context to student discoveries outside class sessions. While I’m yet to master the students’ much-loved GIF feature, Teams has provided another way for me to offer support as they collaborate and apply their new-found knowledge.

It’s been a privilege to work with this class, and I look forward to continuing this important project.

Bibliography

Mars, James. Life of James Mars: A Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Hartford: Press of Case, Lockwood & Company, 1864. Documenting the American South. 1998. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 7 January 2004 < https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/mars64/mars64.html>.

One thought on “The Library and Searching for Slavery”