By Cipperly Good

The Richard Saltonstall Jr. Curator of Maritime History

at Penobscot Marine Museum

As hurricane season heats up, it is becoming clear how connected New England is to the Caribbean when it comes to wind patterns. As we watch hurricanes form in the middle Atlantic Ocean, hit the Caribbean, and then rush along the North American Atlantic seaboard wreaking havoc, we can imagine those same winds, albeit hopefully lesser in velocity, pushing the coastal schooners of Maine back to port. The schooners carried molasses or other Caribbean sugar cane-derived products. The economic winds of the nineteenth century also linked the economies of the Caribbean and New England, wreaking havoc on the laborers in the sugar cane fields—namely enslaved African and Native Caribbean peoples.

A 1830s letter from James S. Kneeland of West Prospect, Maine (now known as Stockton Springs) provides a glimpse of Maine captains in the sugar trade. According to a family history, James S. Kneeland was born in 1813 in West Prospect during the War of 1812, a war fought with Britain in part over the United States’ right to trade with all colonial powers in the Caribbean without restriction. James died by drowning in 1840 in Philadelphia, at the age of 27, leaving behind a widow and young child.[1] Despite his young age, he had risen to become the captain of coastal trading vessels.

March 3, 1837 letter written in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands by James S. Kneeland to his parents. Kneeland Family Box, LB2022.5

At the age of 24, Kneeland captained a schooner trading between various Caribbean and American ports. He traded Maine timber shaped into spars for masts, yards, booms, and bowsprits. The coastal timber reserves of Maine had been logged out by 1830 and lumbermen had to go further into the interior for a ready supply.[2] As he writes in his letter:

“When we left home we had a fine run off the coast into warm weather. But rather a long passage out and pretty rough. We had a passage of twenty five days to Barbados… where we discharged our spars thence to Trinidad and discharged the rest of our cargo to Trinidad. We arrived here [St. Thomas] yesterday… we shall be off tomorrow for Puerto Rico, where we shall take in a cargo of Sugar and molasses for New York… We shall return home from there and if the Schooner does not return I think I shall leave her. It will be about the middle of April before We shall arrive at York.”

Kneeland’s trading voyage took him from West Prospect, Maine to Barbados, Trinidad, and St. Thomas, with projected stops at Puerto Rico and New York City. Explore the map.

Kneeland’s first stop on his trading cruise was Barbados. Barbados was a British colony, whose government abolished slavery in 1833, just four years before Kneeland arrived to trade. According to Brent W. and Richard W. Stoffle’s “At the Sea’s Edge: Elders and Children in the Littorals of Barbados and the Bahamas,” although freed, the African plantation workers lacked access to new land and jobs, resulting in many continuing to live and work on the sugar plantations, albeit with low wages. A Land Purchase Law required that land could only be purchased in large quantities and at high prices, a prospect unavailable to formerly enslaved peoples.

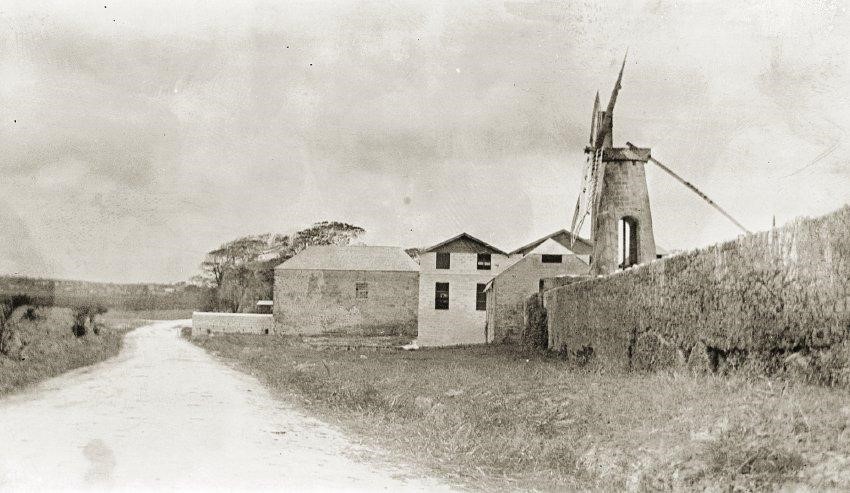

Barbados Sugar Mill, circa 1920. Joanna C. Colcord Collection, LB2003.61.1067

The second stop was Trinidad. Unlike Barbados, Trinidad was a relatively new British colony, joining the British Empire in 1802. Previously it had been a Spanish Colony that was loosely populated by burgeoning sugar and cacao plantation owners, who began in the late 1700s to clear the forests. According to historian Stephen Luscombe, although slavery continued to increase under British rule, the economy was not as dependent on the plantation system when abolition came in 1833. After 1833, the plantations ran under an apprenticeship system that was soon abolished in 1838, just a year after Kneeland’s trading visit. After that, many emancipated Africans chose to move to urban centers rather than work on plantations.

Horse-drawn sugar cane cart driven by Afro-Caribbean workers circa 1920. Joanna C. Colcord Collection, LB2003.61.1272

The third stop, where Kneeland wrote his letter, was St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. Although Britain tried multiple times to occupy the island, Denmark retained ownership in 1837. Slavery would not be abolished until 1848 and the United States would not acquire the Virgin Islands as a territory until 1917. As a Danish colony, the island remained neutral during the early 19th century Napoleonic War between France and Britain and was the largest slaving and distribution port during that period. Sugar plantations dominated the economy, although there was a fall in sugar prices in the 1820s that led to a slow decline. Despite its fall from prominence as a distribution port in 1815, Kneeland’s was not the only American vessel in St. Thomas, as he writes, he found: “Capt. John Cousins in the CANARY and Capt. John Atwood in the MARINER, if you recollect the Brig that Uncle William is in and he is well and hearty.”

Photographer Joanna Colcord, born at sea aboard her father’s sailing cargo bark, led a Red Cross expedition to the US Virgin Islands in 1920. Although the ships had transitioned from sail to steam, the export of local produce continued. Joanna C. Colcord Collection, LB2003.61.1087

The projected next stop was Puerto Rico, a Spanish colony at the time of Kneeland’s cruise. Although Spain abolished the slave trade to its colonies in 1835, slavery continued until 1873 on Puerto Rico. The island had been largely undeveloped until 1830, but the plantation economy producing sugarcane and coffee quickly ramped up, with sugarcane being refined into sugar and molasses for trade with the United States. A royal decree in 1815 had spurred this development by encouraging settlement by displaced plantation owners from former Spanish colonies in the Americas and others loyal to the Spanish Crown and Roman Catholic Church. Another provision of the royal decrees was free trade with any country in good standing diplomatically with Spain. While Kneeland found the import business to be good, he was waiting until he arrived at Puerto Rico to purchase his export goods: “Our cargo did well, spars sold out one dollar per inch but West Indies produce is very high.”

Puerto Rican Tobacco Plantation, circa 1920. The plantation economy continued to prosper in Puerto Rico into the 20th century. Joanna C. Colcord Collection, LB2004.21.59 BL

The Puerto Rican molasses was destined for New York City. Sugar cane juice was extracted and put into hogheads with holes in the bottom where the molasses drained off from the crystallizing raw sugar.[3] Both products were shipped to New York, the former to be refined into white sugar and the molasses to be distilled into rum.[4] In 1835, 16,2000 tons of coastal cargo vessels came from Puerto Rico to New York carrying coffee, raw sugar and molasses.[5] In 1860, the tonnage of coastal cargo vessels had risen an additional 30% to 23,000 tons[6] moving 2,000,000 gallons of molasses from Puerto Rico to New York,[7] making a rough calculation of about 1,400,000 gallons of molasses entering New York from Puerto Rico when Kneeland was in business.

The only other letter we have from James Kneeland in the collection is written from Matanzas, Cuba two years later. Cuba dominated the sugar trade in those years, so it would seem that Kneeland continued in the sugar trade until his death in 1840. The trade of Maine timber for Caribbean sugar profited many sea captains from our area even as it exploited the African and Caribbean workers on the plantations.

[1] Kneeland, Stillman Foster. Seven Centuries in the Kneeland Family. (New York: self-published, 1897). 116.

[2] Albion, Robert G., William A. Baker, Benjamin W. Labaree, and Marion V. Brewington. New England and the Sea. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1972. 141

[3] Albion, Robert G. The Rise of New York Port 1815-1860. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939), 179.

[4] Albion, 180.

[5] Albion, 396.

[6] Albion, 399.

[7] Albion, 180.